The climate crisis won’t wait. Every action taken now has a greater impact than the same action later. Oona Poropudas, Project Manager at the TAH Foundation, explains why real climate impact only happens when solutions are scaled into practice—and why foundations could play a crucial role in addressing the crisis.

When it comes to climate solutions, the biggest barrier is no longer technology—it’s deployment.

“The climate threats are urgent, and all actions taken now create a bigger cumulative effect than the same action later on. Technology and fast-scaling companies have the ability to rapidly change the world, especially by transforming existing production methods and replacing raw materials that are currently dependent on fossil fuels,” says Oona Poropudas, Project Manager at the TAH Foundation.

These themes arise from an EU-funded project, which explores models to scale climate innovations and remove financing barriers. TAH Foundation’s role is to develop solutions to deploying critical climate technologies faster and to direct capital toward accelerating the first commercial projects.

The bottleneck isn’t technology—it’s commercial and industrial scaling

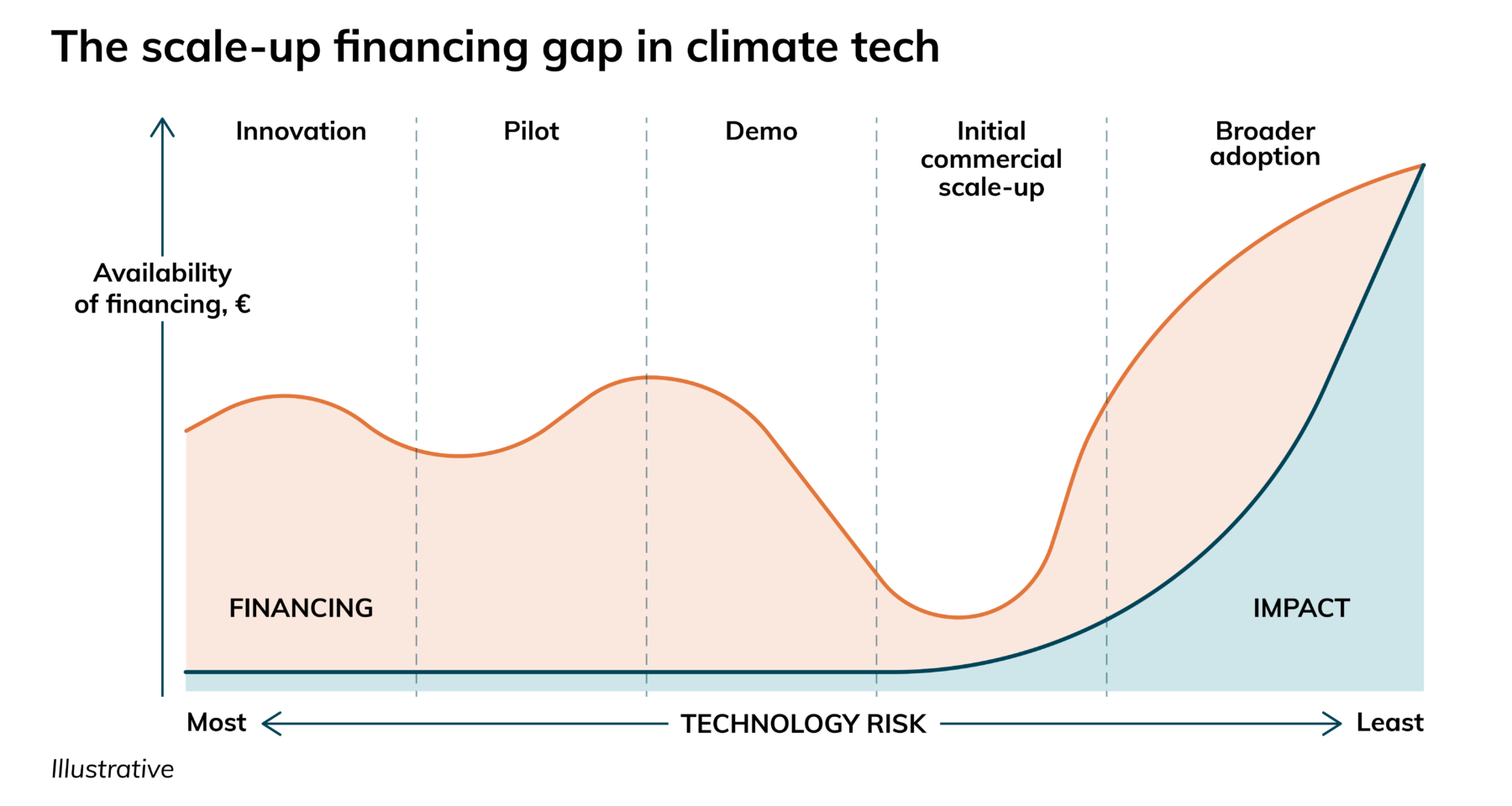

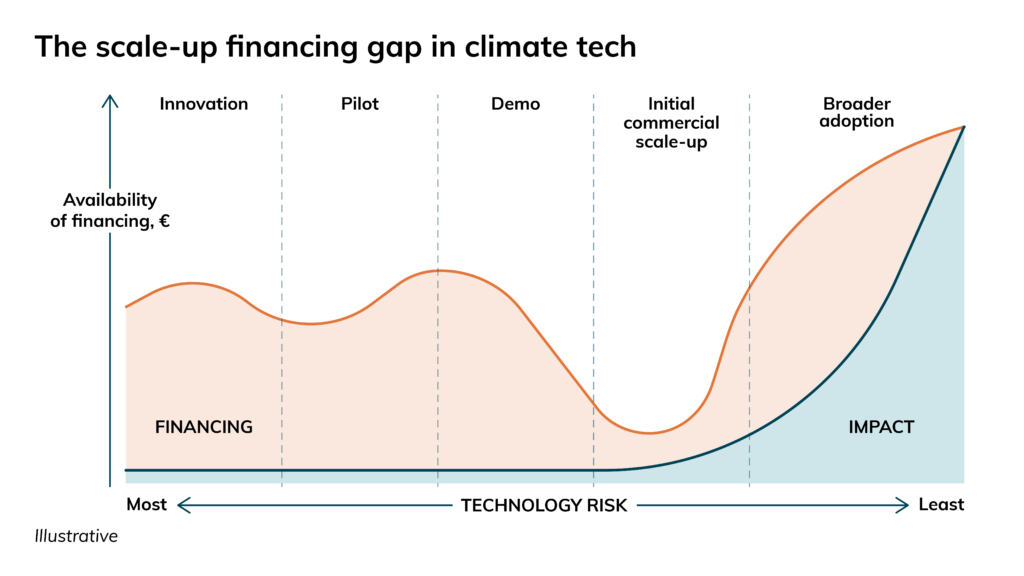

The problem isn’t a lack of inventions. According to a report by management consulting company McKinsey, about 90 percent of the technologies needed for reaching net zero by 2050 already exist. “Too many players—including foundations and venture capital funds—focus on the early stages, like commercializing research and bringing it to market. That is of course important, but if most of the required technologies already exist, the real bottleneck lies elsewhere: in scaling,” Poropudas says.

Venture capital funds are early-stage investors that finance startups. The biggest practical hurdle in the scaling phase is the first commercial scale facility—known as FOAK, or First of a Kind. At this stage, the risk–return ratio is typically asymmetric: the risks are high, efficiency is still low, and returns take time. “It’s not just about the lack of funding. It’s also about whether the company is ready to be funded—whether it has the necessary expertise in infrastructure project development, an understanding of critical legislation and subsidies, land-use permits, guarantees, and strong community relationships.”

In the early tech phase, everything looks like opportunity. Companies are evaluated based on the potential impact, returns, and growth if the company succeeds.

“But when you move into the growth phase and start building physical infrastructure—like a first-of-a-kind plant—you can’t keep iterating endlessly on a small budget. These projects require large financing rounds and they need to hit the nail on the head the first time. The role of risk increases sharply, and the conversation shifts from opportunities to identifying and managing risks.”

Who takes the risk—and who dares to act?

According to Poropudas, moving forward requires not only courage but also a comprehensive understanding of risk.

“Risks need to be understood inside out to map the best ways to mitigate them—reduce where possible and plan what to do if they materialize. It’s also essential to define who should carry which risk. What falls on the developer and what on the construction company? Are there insurances, guarantees or grants that can hedge against downside risks? How much and what type of risks are left to the financiers? In the end you plan for buffers and react to events as they unfold as some risks will always remain unpredictable and nearly impossible to prepare for,” Poropudas says.

Investors’ ability to take risk and invest in these projects can be structurally difficult. Regulation and institutional mandates often limit the ability of many actors to invest in high-risk, high-impact projects. For example, pension funds are obligated to secure future pensions, which steers them toward low-risk investments. Similarly, public investment funds are accountable to taxpayers, which restricts their capacity to take big risks.

“That’s understandable, but it still raises the question: if even public institutions can’t take risks for a better future for their citizens, then who can?” Poropudas asks. “Public funding shapes markets, but as we see in the United States, Finland, and many other countries where the climate agenda has lost momentum—it’s political and cyclical.”

Poropudas notes that around the world, several climate-focused and risk-tolerant financing instruments have been scaled back, with emphasis shifting toward more market-driven, lower-risk funding.

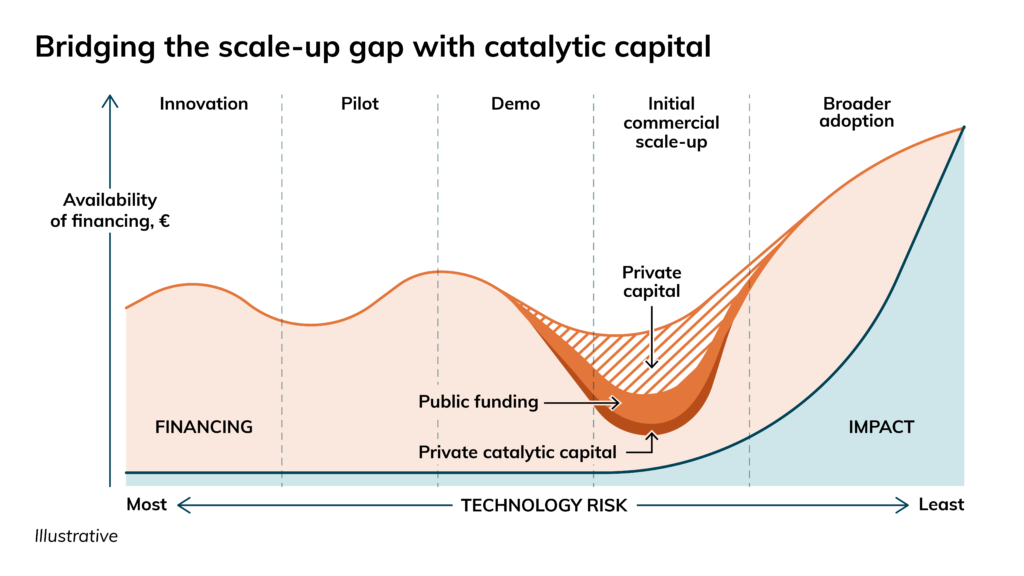

Foundations’ catalytic capital could accelerate climate solutions

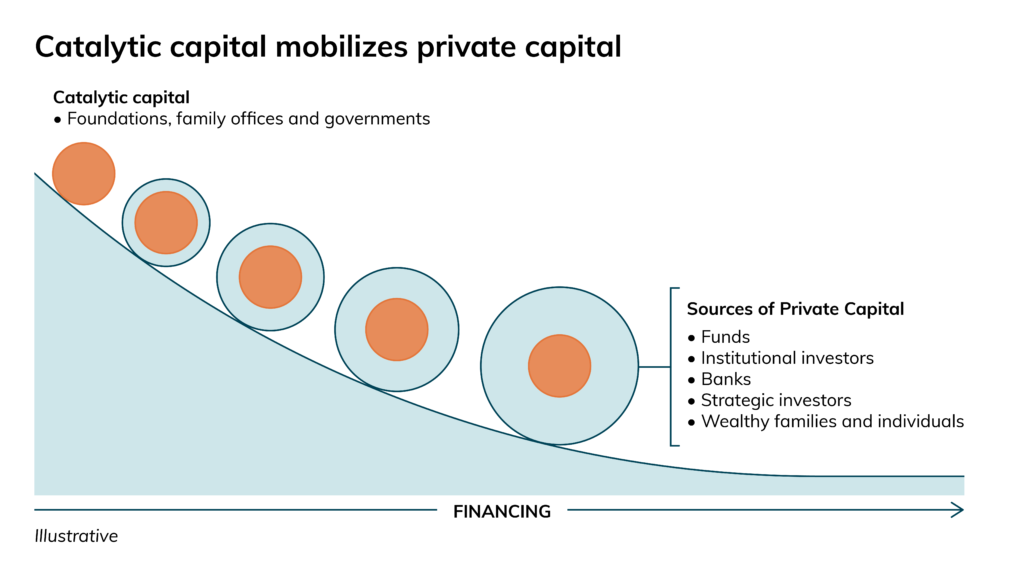

Private catalytic capital—such as that provided by foundations—offers a counterbalance. Catalytic capital refers to impact-driven capital with higher risk tolerance that helps attract other investors and accelerates the development of new solutions. This kind of capital can jump-start projects that traditional investors are not yet ready to fund but that have significant climate impact potential.

“Compared to public financiers, foundations have the ability to move much faster and their time horizon is longer—they think in decades instead of years. These actors are fundamentally impact-driven—at least in principle. Bold players inspire others: when one acts, others follow. Even when the will exists, it takes courage to be the first.”

The role of foundations could be far greater than it is today. “European foundations hold assets worth €650 billion, of which Finnish foundations account for more than €20 billion. If 10–15 percent of that were invested in scaling climate innovations, it would amount to nearly another Tesi, Finnish state-owned investment company, which manages €3.1 billion in investment capital.”

Poropudas points out that a number of structural and cultural barriers slow down catalytic funding by foundations. The most significant are strict and fragmented foundation laws across the EU and foundations’ traditional approach of keeping operational grant funding activities and asset management strictly separate. These silos limit foundations’ ability to create systemic impact, even though impact investing from endowments is a powerful tool. “But this is exactly where courage is needed,” Poropudas says.

In principle, foundations have the long-term perspective and agility to direct risk tolerant capital where it can enable systemic change. But current structures and regulations restrict that flexibility. Catalytic capital belongs where market-based financing alone isn’t enough—and where it can help remove key barriers to scaling, often in the highest-risk phases.

“As Brené Brown says, courage means acting and making choices amid uncertainty and risk,” Poropudas concludes. “That’s exactly what scaling climate solutions requires today.”